by Philip Gross

One of the habits Lewis recognizes in the reading of "the many" and "the unliterary" is the sad practice of only ever reading a book once. Such a reader may be voracious, but he sees no value in revisiting a favorite novel. Usually that reader 'already knows what happened' and does not enjoy reading for bounties besides plot.It is interesting that our enjoyment of games rests so heavily on multiple plays. Even among casual gamers, the usual habit is to play a game several times. We even know 'mono-gamers' like my wife's parents, who play Ticket to Ride: Märklin at least twice daily. Marklin is their current fix, and each such game lasts them a few years. If a 'hobby gamer' only plays a game once, she likely has a surplus of games, or it was not her own copy, or it was awful.

We praise variety in design and play almost as presuppositions for a good game. This is fair—we want a space to make decisions, explore, and create fun. Variety fuels play, be it across hundreds of boards in Dominion or games of Chess. We may all agree that a good game is worth playing more than once. But could there ever be a good game that is designed for only one play?

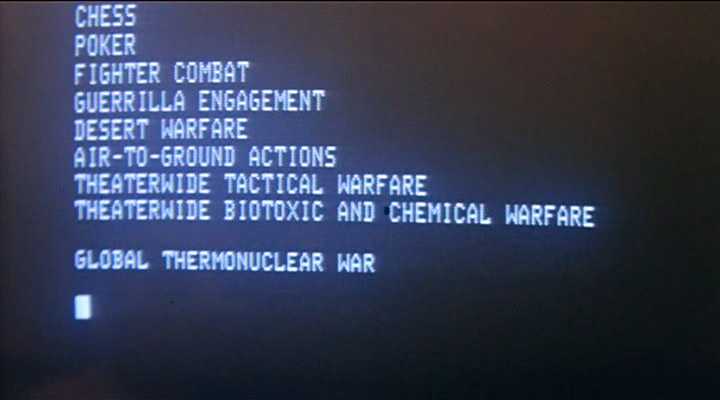

Let's set some parameters. First, we will ignore all considerations of market value. This hypothetical game is commissioned by an infinitely rich donor who will spare no expense. Second, we are not imagining a game that only gets played once because it takes several days to finish. Third, the game is not necessarily disposable or alterable (e.g., Risk Legacy). The game is not a Mission Impossible briefing. Finally, the game is not Russian Roulette or Twilight Struggle with real nukes.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.

I am thinking instead of those challenging works of art that shake us to the core, and that most sensible folks revisit just once every ten years. For instance, I bought Schindler's List on DVD several years ago, but I haven't watched it more recently than several years before that purchase. Similarly, I would love to read Moby Dick again before this life is through, but I am not currently eager.

Isn't it a little strange that so few games aim for this artistic space? I can only think of a few examples that don't quite fit: Phil Eklund's near-academic designs, and some pieces commissioned by MoMA. If you know of others, I would be interested to hear.

There are market issues. Gamers expect re-playability, and the casual public does not expect art. Also, some thematic content is nearly impossible to represent in a satisfying game experience. For example, it would be very hard to design a game centered on religious beliefs, lest God play with dice or every player win by entering heaven. Yet a great deal of traditional art is concerned with the sacred.

Case Studies

Over the last year I had two first-time experiences with games that were so good, I am considering never playing them again. Neither fits the hypothetical game we are imagining, but they serve as interesting case studies with some shared value.

My buddy Patrick taught me how to play Combat Commander: Europe. I began the game intimidated because my experience with traditional war games is limited. To my surprise, CC holds much in common with a heavily-themed tactical minis game like Warhammer 40k, which I grew up with. The rules in CC are more solid, and the card play offers interesting decisions.

Our game played out with much hollering and story-telling. Major objectives appeared in unexpected but wholly defended portions of the board. Squads threw satchel charges to clear a bunker, only to walk right into trip mines. My army spawned a heroic young lieutenant who proceeded to make a fool of himself, and a stunning private who held the line, gained access to radio equipment, and then called in devastating bombardments within twenty yards of his position. The trash talk culminated as we held on by fingernails. Nearly every endgame condition was met before I eked out a win in the last possible moment.

RavenCon in Ohio (http://www.ravenwoodcastle.com/ravencon.html) was an excellent choice for our first convention. On the first night, amidst a delirious flow of games, one of our new friends suggested Betrayal at House on the Hill. I was Flash, a numbskull jock whose primary strategy was searching the top floor for a shotgun. We all cracked wise as the middle school girl got buff in the fitness room, and the mystical elevator traveled to repeated dead ends. Our laughter was strong, but the situation became hysterical when our friend revealed himself as the Zombie Overlord.

Several zombies clawed up through the floorboards and shambled through the house. Friends’ brains were devoured one by one, starting with the ten-year-old boy. Flash had the mysterious medallion, so only he could harm the Zombie Overlord—who was two stories below. First, several zombies attacked Flash at once. He wielded a deadly spear with great prowess. After each roll to attack and defend, he declared his almighty catchphrase in a Baywatch baritone:

“Flash is here.”

Flash didn’t take a single hit. He decapitated several zombies. A friend scurried up from the basement with the glowing zombie defense doo-hickey in hand, and was then consumed mere spaces from Flash. But never fear, dear reader. Flash’s faithful dog retrieved the doo-hickey, which enabled Flash to face off and demolish the Zombie Overlord in two swift blows. We laughed and laughed, then recounted the whole tale and laughed some more.

Conclusions

These two game plays share some common threads that might inform our hypothetical one-shot game. First and foremost, all the players were receptive to the game state and each other; we were all looking for fun in the same way, and the games encouraged it. Second, each game included more tactical decision-making than strategic. Combat Commander might support more depth across multiple plays, notably in the card play. Yet both games, given a good teacher, are easy for an experienced gamer to explore. Each game contains multiple random elements, which were sometimes controllable (CC) and always contributed to the emergent narrative. Finally, yes, I did win both games, but all players involved reported a jolly good time after the game was over.

Our hypothetical game need not be terribly serious. The primary reason I have not sought out these games again is that I’m afraid of chasing the first, great high like an addict. A one-shot game that takes itself too seriously could easily fall into teaching maudlin lessons about ‘the way life really is’. Perhaps that severe, dramatic Schindler’s List game is possible. The fact no such game exists does not disprove games are art, but it would be a great boon for games’ acceptance as art if one did.

Cheers,

-Phil